Tom Poore © 2018. All rights reserved. Classical guitar lessons in Avon, Beachwood, Solon, South Euclid. Contact me at augustineregal@yahoo.com

“Simplicity is complexity resolved.” — Constantin Brâncuși

When we watch a virtuoso play, it looks easy. The left hand glides smoothly from place to place. The right hand seems to do almost nothing. The artist’s face betrays neither strain nor doubt. Everything flows with supple beauty. And in truth, it’s often just that. It looks easy because, for the artist, it pretty much is.

This ease, however, is hard won. We who only see artists in performance aren’t privy to the hours of solitary labor in the practice room. We see and hear the result, not the process. For listeners, this does no harm. It’s enough for them to enjoy the performance. But for those learning to play, having the process hidden can be deceiving. Too often we see virtuosos as a breed apart. They’re different. They’re gifted. They learn with the ease of gods. For the rest of us, it’s grueling work. Progress creeps imperceptibly. Usually we fall short.

In part, this is a fallacy. Yes, virtuosos may have innate talent. (Although a surprising number of them deny this.) But they, like us, have to work. It’s likely they put in more time than us. More than this, however, is how they work. Quality, not quantity, is the crucial difference. Virtuosos don’t play better simply because they practice more. Virtuosos play better because they practice better.

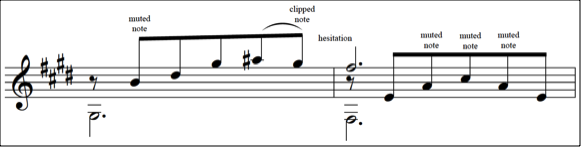

Effective practice boils down to an attention to detail far beyond what most students think is necessary. When confronted with a problem, patient students are willing to put in the time. By itself, however, time is no guarantee of progress. What’s crucial are the investigative skills you bring to bear on any problem you face. To illustrate, here are two measures a student of mine, Jeff, was having trouble with:

When he went from the fourth fret bar to the second fret bar, Jeff couldn’t avoid a noticeable break in the musical line. Further, although he could play bar chords, they were still a work in progress. So getting clean notes on every string of each bar was a challenge.

When faced with such a problem, most students repeat the offending passage over and over again. Do it enough times, they assume, and the problem goes away. Well, sometimes it does. But often it doesn’t. And even if it does, students who rely on mere repetition waste time they could save if they practiced more efficiently. Time wasted is time that might have been better spent.

So I didn’t tell Jeff to mindlessly repeat the passage. Instead, we stopped.

(That’s important.)

Then I asked Jeff to play the two measures once and listen carefully. Here’s what we heard:

That’s a lot of bad stuff in one passage. And the average conscientious student would buckle down and attack all the problems at once. But that’s not what Jeff and I did. Rather, we looked closely at the problems. We soon realized each of these problems had different causes:

• The muted notes were the result of poorly set bars.

• The clipped G# was due to letting go of the fourth fret bar too soon.

• The hesitation was the result of confusion and anxiety about getting to the second fret bar in time.

So Jeff faced three distinct problems, each requiring its own distinct solution. Juggling three problems at once is far too complex. Instead, Jeff needed to resolve each problem one at a time. When confronted with multiple problems, it’s sensible to start with whatever seems most basic. Jeff and I agreed that the most basic problem he faced was placing a bar so all the notes sounded cleanly. Thus, he started there.

Solving Problem 1

Jeff carefully set a fourth fret bar, slowly playing each string that needed to sound to ensure no notes were buzzed or muted. (He started with the fourth fret bar because it’s easier than a second fret bar. The strings are a bit stiffer at the second fret.) If he heard any bad notes, he released the bar and reset it, making tiny adjustments to find the best position. When he found a position that gave clean notes, he dropped his left hand and began again, trying to precisely reproduce the best position. (When you do something right for the first time, your next step is to get it right consistently.) He didn’t consider the problem solved until he could play the bar perfectly ten times in a row.

Jeff then did the same thing with the second fret bar. Again, his goal was to set and play a clean bar ten times in a row. As it happens, Jeff solved this problem quickly. He’s not a novice when it comes to bar chords. He just needed to clean things up a bit. But if he needed more time to clean up his bar chords, then so be it. There’s no point in moving to another problem if you can’t solve the one before it.

Solving Problem 2

Jeff’s next goal was to avoid clipping the final G# of the fourth fret bar. Obviously, in his effort to get to the next bar chord, he was releasing the fourth fret bar too soon. So I suggested this little procedure:

1) While holding the bar, play the A# to G# slur at a slow tempo. Be sure to hold the G# for a full half beat—the same exact duration as the A#.

2) Merely release the bar pressure. Don’t lift your fingers off the strings and don’t move off the fourth fret bar.

3) Now lift the bar off the strings and slowly move to the second fret bar. Don’t try to get there in strict time. Instead, take all the time you need

to reset the bar perfectly at the second fret.

Jeff’s goal was to avoid the anxiety of a quick shift. (Anxiety tends to make us tense. Nervous tension makes our movements less easy and precise.) By taking his time, Jeff could train himself to make the shift in a calm and fluid way.

While doing this, however, a new problem arose. When Jeff lifted his bar finger off the strings, he inadvertently sounded the open strings. This is a common problem for guitarists. The solution requires some creativity. Jeff and I experimented with “peeling” his bar finger off the strings—that is, lifting the finger so the tip comes off first, followed by the length of the finger down to its base. By peeling his finger off the strings, Jeff learned to eliminate the extraneous open string notes. Again, he practiced this gradually, first doing the peeling movement slowly, then speeding it up as he became more fluent. By the way, he peeled from tip to base because the last played note of the bar was on the first string. If the last played note was on the sixth string, then he’d reverse the direction of the peeling motion. Remember, the whole point of this was to avoid clipping a note.

Momentarily sidetracked by the extraneous noise problem, Jeff soon solved it and returned to the problem of clipping the G#. Again, he did his three step procedure: play all notes of the fourth fret bar, stop and merely release the pressure, then carefully and precisely move to and set the second fret bar. Again, he took all the time he needed to do this perfectly. His goal at this point wasn’t to keep strict time. Rather, it was to get perfectly sounding notes without a hint of nervousness.

An Aside of Earth-Shattering Importance

Let’s pause a moment and reflect on an iron rule of practicing: you become what you repeat.

That’s true for everything you repeat, not just finger movements. Repetition also locks in your emotional state as you practice. If you repeat nervousness, then you’ll build it into your playing. Even if your physical movements are flawless, ultimately they’ll be sabotaged by the nervousness you’ve diligently (though unintentionally) hard-wired through repeated practice. You can literally practice yourself into permanent nervousness.

For this reason, you should be acutely aware of nervousness as you practice. Nervousness isn’t a trivial byproduct of practice. Rather, it’s a devastating flaw to root out. It’s as important as a missed note or a memory lapse. In fact, it’s probably more important, since nervousness itself can generate an endless cascade of missed notes and memory lapses. So you should treat it as a central focus of your practice. During every minute of practice, you’re on a search and destroy mission for the slightest bit of nervousness.

— (This essay is a work in progress.) —